Talk at the Institute for Studies on Latin American Art (ISLAA), January 18, 2025

Can we take Benedit seriously? Or is his work more of a joke, a one-liner that has gone stale? Or, conversely, is there more to the lightness and humor than meets the eye? In 1968, just months before Tucumán Arde –a milestone of Latin American political art– and practically simultaneous with the first showings of Hélio Oiticica’s parangolés in Brazil, Benedit’s Microzoo show at Galería Rubbers, Buenos Aires, featured a series of pieces that adopted, as did Oiticica’s, the form of the habitat-labyrinth at the same time as it reflected on the interface between communicational stimuli and patterns of behavior. But rather than, as in Tucumán Arde, tackling these issues by attempting to short-circuit neocolonial-capitalist ideology using the disruptive strategies of avant-garde art or, as in Oiticica’s post-concretist work, wager on the sensorial immersion of the spectators-participants, with the artwork as a kind of catalyst triggering individual and collective ways of being-otherwise, Benedit’s work, at least at first glance, appeared to take us away from what Roberto Jacoby describes as the galloping race, in less than half a decade, from the formal concerns of minimalist abstraction to the outright juxtaposition of art and politics in Latin America. Microzoo, instead, contained artificial habitats for living organisms including a plexi glass anthill and other receptacles for lizards, fish and turtles, as well as small nurseries for plants in different states of germination. The provision of light and food imposed on these certain types of behavior in conditions of an artificial environment, the learning of which visitors could observe as it occurred. In Benedit’s own words:

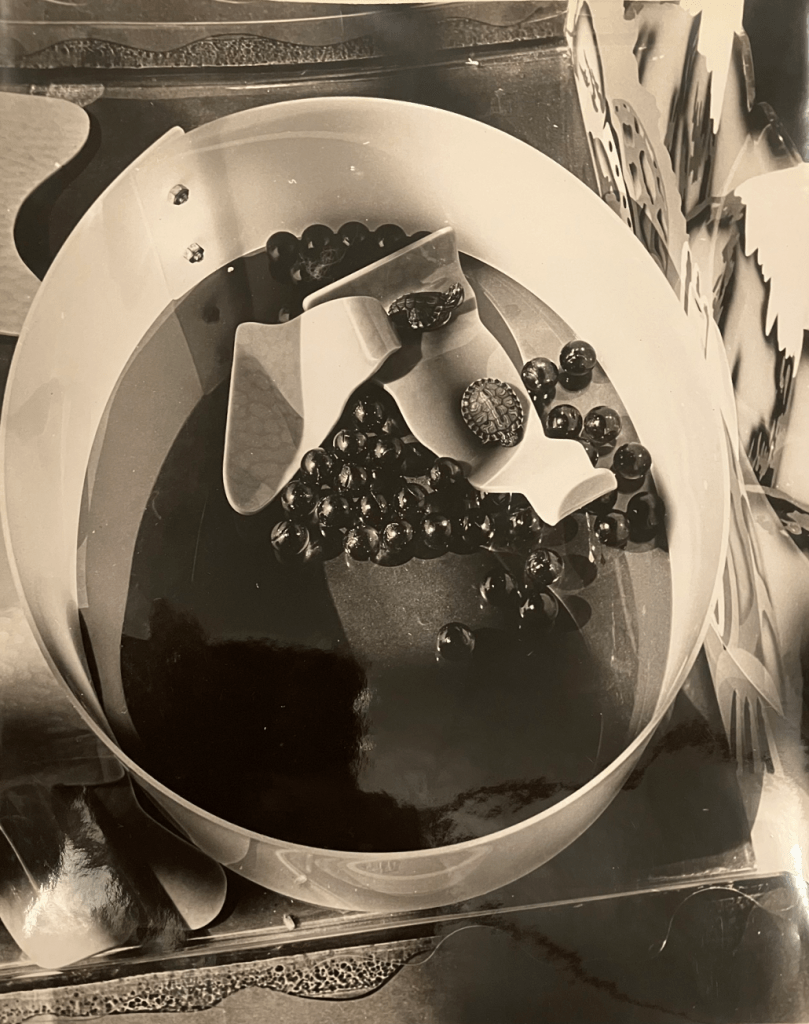

Luis F. Benedit, Habitat for water turtles (1968). Courtesy ISLAA archive.

Now, this supposedly didactic nature of the habitats and labyrinths raises several questions. Who exactly is the one “learning” from the device? Is it us spectators or rather the non-human beings who adapt their lives to the conditions of the artifice? In other words, if there is something we can learn from other existents’ learning, is this lesson really about the natural order or not rather about its accomodation to artificial conditions? But also, how is this behavioral modification different from our own aesthetic response to the artwork, if plants and animals effectively forge from their encounter with the “ecological sculpture” new ways of being in the world? Are they the real connoisseurs?

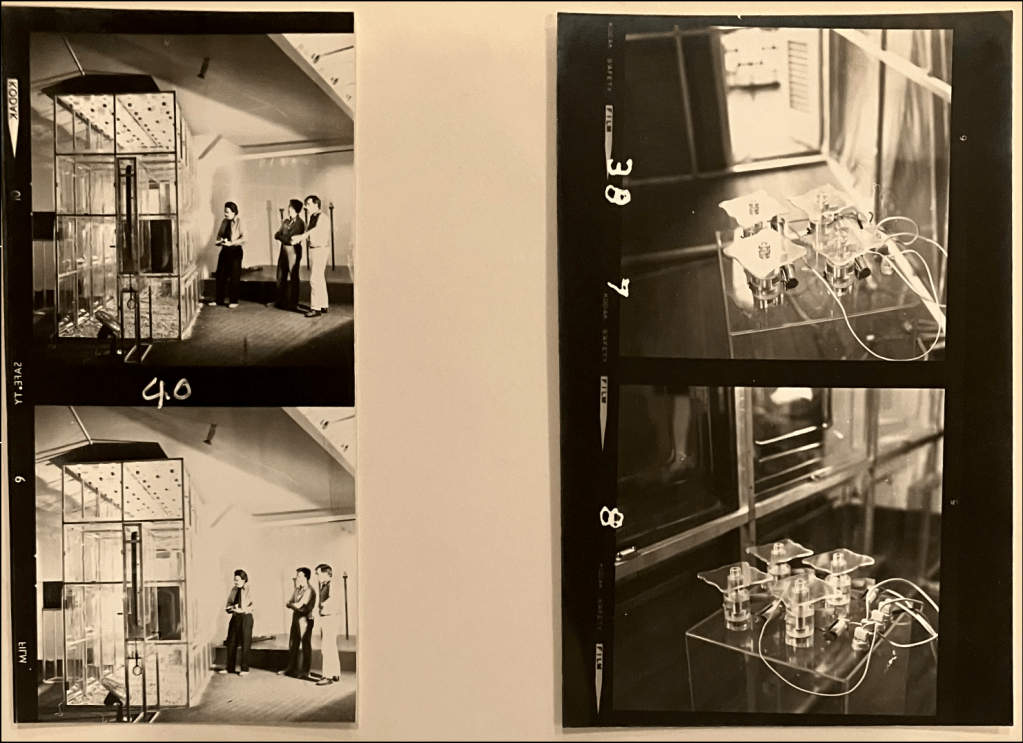

Effectively, then, we might think of the successive phases in Benedict's work as early forerunners of bioart and ecoart, and thus as “political” in their own, anachronistic fashion. In 1971, returning to Italy where he had previously completed a degree in landscape architecture, Benedit exhibited Biotrón at the Venice Biennale, created together with the biologist José Nuñez and which, after the exhibition was over, was reinstalled at the Faculty of Exact Sciences of Buenos Aires University. It consisted of a transparent plexi and aluminum frame containing at one end a transparent honeycomb with four thousand live bees for which, inside the receptacle, an “artificial meadow” with electronic flowers secreting a sugary nectar, provided nutrition. At the opposite end was an exit tube to the Biennal’s gardens, allowing the bees to choose between foraging for food outside or staying inside feeding on its artificially generated equivalent.

The following year, on occasion of his solo show at MoMA, Benedit premiered Fitotrón, a device where, through the manipulation of the variables of light, humidity and temperature, one could observe the plants’ reactions in their adaptation – or not – to these environmental changes, a proposal the work shared with Laberinto vegetal, from the following year, a black plexi box with germinating seeds at one end and a forty-watt lamp at the other. In their growth towards that light source, triggered by phototropic attraction, the plants had to navigate an itinerary that branched into two alternative paths (right/left), leading them either to death or survival.

The disconcerting, even revulsive effect these works provoke had to do, it seems to me, not just with having living beings in museums and galleries (instead of their usual places of residence in the human environment such as laboratories, gardens or zoos). Rather, it stems from the provocative confusion between artistic and scientific modes of encompassing and containing those lives. The opposition that gives this work its constitutive tension is not, or not only, that of nature and artifice; rather, it is the distinction between different forms of artifice and their respective effects of nature. Biotrón is perhaps where this difference between regimes of artificiality is most clearly marked: the point here is not there, as art historian Carlos Espartaco (1978: 13) claims, about “making [the bees] fluctuate between a natural environment (gardens) and an artificial one (the biotron)” because a garden is of course no less an artificial medium than an electronic meadow, only it belongs to a different regime of administration of the living. Rather than a contrast between nature and artifice, the Biotrón stages a reflection on the senses of the natural that a certain artificial order entails. Between the artificial landscape of the garden and the electronic meadow, we move from a relationship mediated by representation as imitation to one of substitution of certain relations and functions, that is, to what Tom Mitchell calls “the age of biocybernetic reproduction” (Mitchell 2003: 483-84).

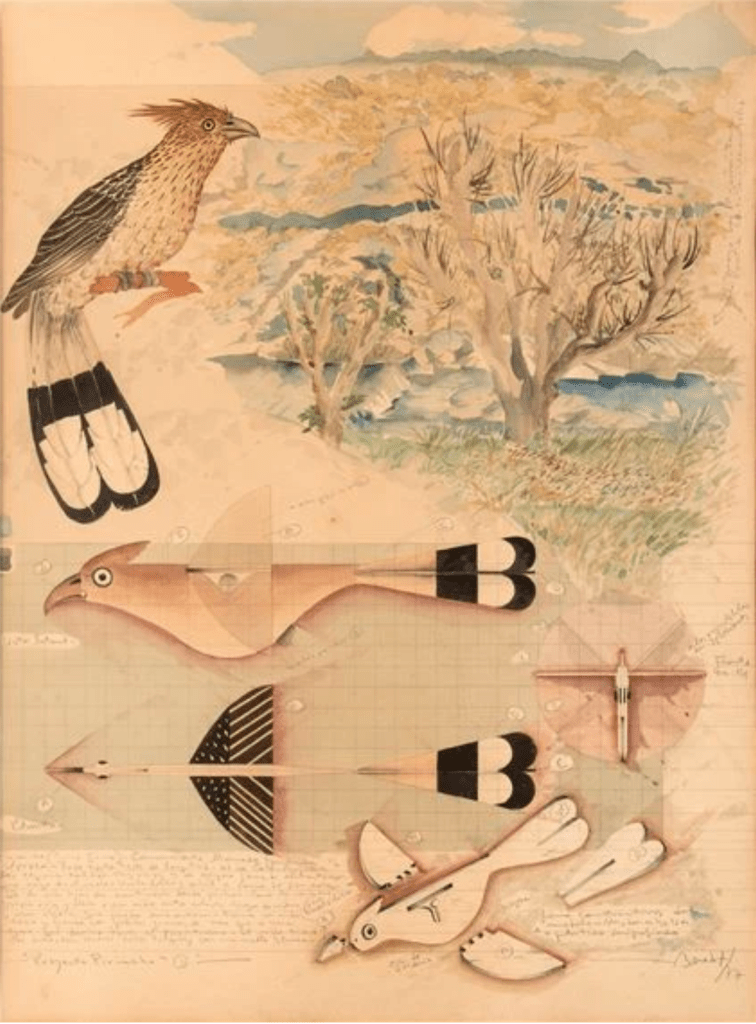

In his later work, Benedit would highlight this archaeological dimension of investigating the modern regimes of nature. After Laberinto vegetal, he effectively stopped working with living organisms to dedicate himself instead to their analytical “despiece” or “dismantling”: thus, in a series of drawings of Argentine birds, the pencil and watercolor technique of nineteenth-century naturalism is juxtaposed with the technical drawing, which “reconstructs” the flying organism through complex robotic mechanics. There is also a return to the objectual dimension as in Furnarius Rufus from 1976 –a wooden frame with an ovenbird’s nest containing an embalmed bird– and on to the collection or the museum as in Campo (1978), a kind of “Exposición Rural” or agriculture show documenting the human-animal assemblage of production mediated by biotechnology. In paintings, photographs, glass and wood containers and objects modeled in resin, this museum of Pampean biopolitics subjected to a similar kind of analytical “despiece” as the bird-robots an entire regime of human-animal life, broken down into individual elements such as a set of boleadoras, batons, stirrups, bridle and muzzle, castrating scissors and the photo of a dead pedigree bull next to the artificial insemination pills in which its frozen semen remains preserved. In the following decade, Benedit would go even further back in his archaeological approach, turning to the pictorial production of the Pampa landscape and 'recreating' works by nineteenth-century artist León Pallière such as Un nido en la pampa, Indios del Gran Chaco and El payador (1984-85), among others. Rather than an expression of rural nostalgia, this return to “picturesque” landscape dismantles and reassembles it as one more technology for the administration of the living, an analytical “dismantling” to which Benedit subsequently also submits the Patagonian expedition of Fitz Roy and Darwin (1831-36) in his multi-installation and artist’s book From the Voyage of the Beagle (1987).

Following the path opened by Benedit, today’s bio and ecoartists are also frequently a kind of archaeologists of the scientific forms of capturing and transforming life. By introducing an aesthetic kind of self-reflexivity into the spaces, procedures and terminologies of the “natural sciences”, bioart and ecoart also call into question the founding biopolitical division of modernity, the divide between nature and culture according to which, as Bruno Latour has argued, the essential truth of nature can be revealed to scientific reason precisely on condition of remaining absolutely external to the cultural (Latour 1993: 104-05). Hence, Benedit’s early “invasion of the laboratory”, his reenactments of the scientific procedures of the experiment, the journey and the collection, also have a (bio)political dimension, in their production of unspecific discourses and statements: these works do not become science, but neither can they be clearly assimilated to art in terms of their procedures and formal affiliations, nor, finally, can they be reduced to political messages of ecological militancy or criticisms of biotechnology. Science, art and politics come into play here in a deliberate un-specification of the artwork’s objectual form and institutional location. Perhaps we should, in fact, think of its aesthetic dimension, if we still wanted to call it that, more than anything as that vector of unspecification the material and discursive arrangement of Benedit’s works project, which is why the dimension of irony and laughter is not coindicental but actually key here: it allows us to make light of the art-science border, to the effect that the living spills out over them.