On January 25, 2019, just after 12 p.m., the collapse of Dam 1 at the Córrego do Feijão iron ore mine near the town of Brumadinho in Minas Gerais, Brazil, released a tidal wave of twelve million cubic meters of toxic mud into the Paraopeba River, the source of about a third of the provincial capital Belo Horizonte’s water supply (fig. 1). At least 250 people were buried alive, among them most of the miners on their lunch break in the company cafeteria just underneath the dam.[1] Dam 1, identical to another that had collapsed only three years prior at the nearby mining town of Mariana, killing nineteen people, was being operated by Vale S. A. (formerly Vale do Rio Doce), the world’s third-largest mining company with operations all over Brazil as well as in Angola, Peru, and Mozambique. In 2018, the year before the Brumadinho dam collapse, the company posted a market share of around US$80 billion, outstripping even Brazilian banking and oil giants Itaú and Petrobrás.[2] In fact, to call Dam 1 a dam already requires a stretch of the imagination. The structure was a so-called tailings dam, essentially a hardened cake of solid by-products from strip mining, which are channeled into an artificial basin. This semiliquid mass, loaded with high levels of mercury and other extremely toxic elements, is in turn contained merely by dirt mounds or by dikes built directly on top of the already hardened residues underneath. Tailings dams are highly vulnerable to liquefaction caused by chemical reactions beneath the surface or by the seepage of rainwater into the lower sediments through cracks in the structure.[3] According to the BBC, Brazil currently has 790 such mining dams, 198 of which are classified as at the same or higher levels of risk of collapse than Brumadinho. But since almost half the dams operating in the country have not yet undergone any kind of risk assessment, this number in fact amounts to more than 40 percent of all dams inspected.[4]

Brumadinho, Minas Gerais, February 17, 2019. Photograph by Vinícius Mendonça-Ibama. Wikimedia Commons.

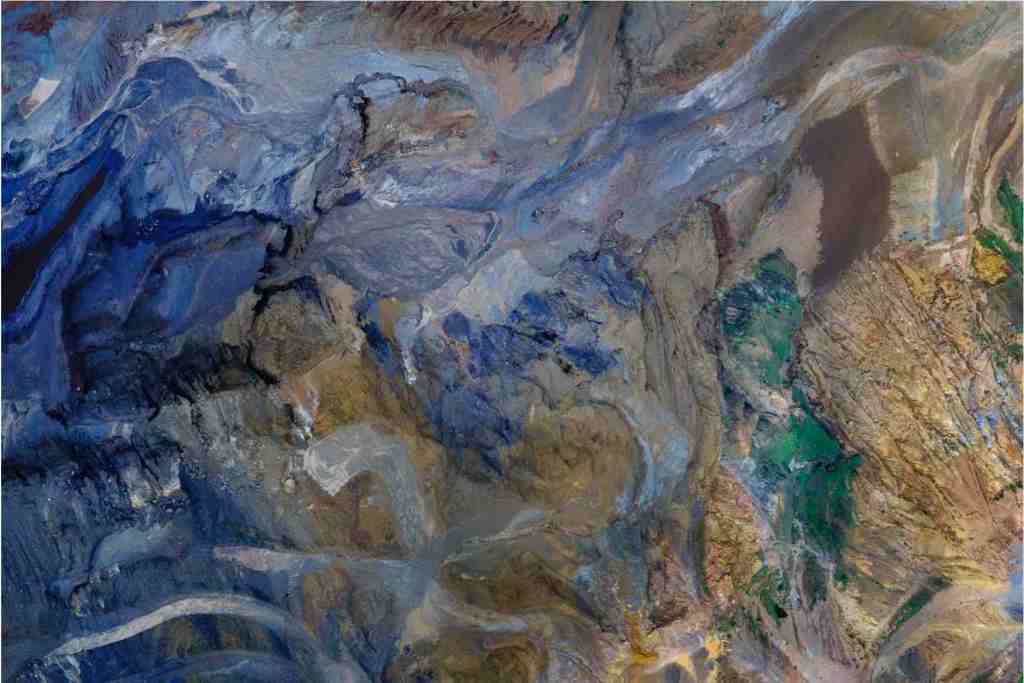

Brazilian artist-activist Júlia Pontés, herself a native of Minas Gerais, has used aerial photography, shot from remotely operated drones, to document the environmental impact of strip mining and tailings dams, including images of the disaster sites of Brumadinho and Mariana. Over several years, Pontés has researched and photographed over a hundred tailings dams and open-pit mining sites all over Brazil, producing eerily beautiful images that recall the post–WWII “biomorphic abstraction” of the Cobra group or the chromatic fields of North American abstract expressionism in the 1950s and 1960s (fig. 2). What kind of poetics of form, or perhaps even the collapse of form altogether, Pontés’s images prompt us to ask, is at work when a central element of nonfigurative Western art makes its uncanny return in the afterlife of landscapes destroyed by extractive capitalism? If abstraction had wagered on the free play of color and volume as expressing the vital impulses of living matter in ways more immediate than mimetic figuration had ever been able to achieve, are the wastelands left behind by extractivism therefore also the cemetery of aesthetic modernity? How to make sense, indeed, of the cruel irony of mining corporations taking to heart the passage from figure to abstraction in the Western art history of the nineteenth and twentieth century—the very same period, of course, that also saw the rise of fossil capitalism—only to force abstraction to become itself the very expression of an earth that can no longer be taken in as landscape? Are the Cézanne-like hues of blue, green, and brown on Pontés’s aerial picture of the strip-mined mountains near Brumadinho yet further proof of, as Bruno Latour puts it, “the great universal law of history according to which the figurative tends to become literal”?[5]

Júlia Pontés, Ó Minas Gerais / My Land Our Landscape #6 (2019), showing Serra Três Irmãos near Brumadinho, MG. Photograph courtesy of the artist.

This book asks what comes at the end of landscape. I mean this in both a historical sense—in terms of the expressive modes and strategies that emerge at a moment when the landscape form in its pictorial, poetic, or architectural iterations fails to account for the ways in which the environment confronts and responds to human action—and a very literal sense: what kinds of agents, substances, and forces come into play once the ground has, quite literally, slipped from under our feet? What Pontés’s images get hold of are, in fact, the very assemblages that living—and dying—things as well as the stuff around them enter into once the heavy machinery of capital has abandoned the scene of extraction. The physiochemical reactions we see on the photographs as fields of color are, at ground level, the work in progress of bacterial agents, lichens, chemicals, mud, rock, and fungi that manifest what anthropologist Anna Tsing calls the “emergent effects of encounters” in the aftermath of ruination. In the abandoned asset fields of extractivism—the spaces that Steve Lerner calls “sacrifice zones”[6]—new “patterns of unintentional coordination develop in assemblages,” as Tsing suggests. “To notice such patterns means watching the interplay of temporal rhythms and scales in the divergent lifeways that gather.”[7]

Then again, the mode in which Pontés’s photographs catch a glimpse of these emergent assemblages of survival in the afterlife of capitalist ruins is not so much that of abstraction as it is, rather, the shift of the point of view away from that of the landscape form. The latter, in fact, had been no less an effect of artifice than Pontés’s drone-based, disembodied camera-eye: its enabling fiction—its “founding perception,” in art historian Norman Bryson’s elegant expression[8]—had been the evacuation of time and movement and the disavowal of the painted surface as a site of production, as well as the abstraction of the observer’s body into a monocular lens mirroring the point of flight of the diamond-shaped visual field thus laid out by the image. The landscape view, in other words, actively erases the “patterns” and “temporal rhythms” in which assemblages express themselves, replacing these with finite, monadic, and mutually separate objects. To unmake this object effect, a change of scale is required, one that unmoors vision from the monocular beholder of landscape and instead “zooms out” (or in) toward the planetary or the fleshly and material, as in Pontés’s images, where we never can be completely sure if we are actually too close or too far away to see things as objects. Yet in the place of objects, what surges before us in these pictures, blurring the boundaries between fields of color that bleed into one another, is none other than what ecological historian Jason Moore calls the “Capitalocene”: that is, the “double internality” represented, on the one hand, by “capitalism’s internalization of planetary life” and, on the other, by “the biosphere’s internalization of capitalism.”[9] The spillages, blurrings, and juxtapositions between fields of color on Pontés’s photographs are the chronicle of this making and unmaking of a “historical nature” fueled by the extraction of matter to produce surplus value, as a result of which existents of various kinds (including deadly toxins) enter into constellations of life and nonlife, of “hyperobjects” that exceed the orderly frame of landscape.

“Hyperobjects,” as eco-philosopher Timothy Morton has pointed out, break down the very idea of an “environment” that surrounds “us” in much the same way as landscape’s founding perception had arranged the world object around the all-commanding gaze of the subject: “In an age of global warming, there is no background, and thus there is no foreground. It is the end of the world, since worlds depend on backgrounds and foregrounds.”[10] We could call this no longer passive but actively and unpredictably responsive constellation of organic and nonorganic beings and materialities acting in concert the “irruption of Gaia”—a name first suggested in chemist James Lovelock’s and biologist Lynn Margulis’s coevolutionary hypothesis from the early 1970s. Gaia’s irruption is a radically materialistic response to the malignant idealism of capital, which, Isabelle Stengers argues, is “a power that captures, segments, and redefines always more and more dimensions of what makes up our reality, our lives, our practices in its service” at the same time as it remains “radically irresponsible, incapable of answering for anything” (italics in original). As we face Gaia, Stengers concludes—or the hyperobject that such a name, just as those of Capitalocene, Anthropocene (or indeed hyperobject) struggle to call out—we are no longer “only dealing with a nature to be ‘protected’ from the damage caused by humans, but also with a nature capable of threatening our modes of thinking and of living for good.”[11]

In this book, rather than discuss these questions in the abstract, I want to follow Pontés’s lead and turn to the sites of extraction—the violent, messy encounters and overspills that take place between human and more-than-human histories on the commodity frontiers of the Global South—from a vantage point that is both wider and narrower than the landscape view. Let us, then, return briefly to Brumadinho’s toxic ground to elaborate on what I mean by the “end of landscape.” If you were wondering “what to do in Brumadinho,” topping TripAdvisor’s list of local attractions (with 8,407 reviews to a mere 79 for the runner-up, the Ostra waterfall) is the Inhotim Contemporary Art Institute and Botanic Garden, billed as “one of Brazil’s most important contemporary art collections and the largest of its kind in Latin America” (TripAdvisor). Founded in 2004 by mining magnate Bernardo de Mello Paz and spreading out over nearly two thousand acres, about half of which are marked as preservation areas, Inhotim is home to one of the most spectacular contemporary art collections worldwide, featuring pieces by, among others, Olafur Eliasson, Anish Kapoor, Thomas Hirschhorn, Doris Salcedo, and Cildo Meireles, many of them site specific and displayed in more than two dozen free-standing pavilions designed by international star architects. Set in lushly gardened grounds created by Pedro Nehring and Luiz Carlos Orsini after an original blueprint from Roberto Burle Marx, Brazil’s premier landscape architect (including his signature monochromatic flowerbeds shaped in “biometric curves”), some of the collection’s most spectacular works echo the garden’s own interest in the relations between organic forms and the aesthetic legacies of modernist art. Cristina Iglesias’s Vegetation Room (2012), for instance, a kind of inverted white cube whose stainless-steel walls reflect the surrounding forest, invites visitors into a maze of sculpted artificial foliage at the heart of which they encounter a plumbing-powered waterfall: a reference, if somewhat tongue-in-cheek, to Hélio Oiticica’s seminal ambient installation Tropicália (1967) replacing the latter’s concern for mass culture in a globalized mediascape with a witty reflection on the artifice of nature in a thoroughly technified planetary interior. Perhaps the most iconic of the site-specific pieces, Doug Aitken’s Sonic Pavilion (2009), subtly acknowledges the extractive historical geography of the location, centering as it does on a seven hundred–feet-deep hole drilled into the ground and spiked with microphones that transmit and amplify the sonic emissions from the subsoil into the glass-sheeted, circular chamber on top.[12]

Inhotim, we might say, pressing our point only slightly, places itself quite explicitly at the end of landscape, the legacy of which it both celebrates and claims to bring to its culmination and apogee. Landscape, in cultural geographer Denis Cosgrove’s authoritative account, emerged contemporary to, and in close interrelation with, the twin processes of capitalist primitive accumulation—the expropriation and enclosure of rural commons all over Europe and the violent establishment of overseas colonies tasked with supplying the “raw materials” (foodstuffs, minerals, human work-energy) fueling industrial modernity in the North. As a “way of seeing” that also “represents a historically specific way of experiencing the world,”[13] landscape was both fundamental to the emergence of the autonomy of art—as relieved from its liturgic or courtly functions of conveying founding narratives for Church and Crown—and closely interwoven with innovations in engineering, agronomics, and even double-entry bookkeeping (not for nothing, landscape painting first blossomed in overseas trading hotspots such as Venice and the Netherlands that were also pioneering drainage and flood protection technology). Landscape rendered the land (and those inhabiting it) the object of an outside beholder’s aesthetic experience or technical expertise. The viewer’s visual pleasure in front of the landscape image mirrors the absentee landlord’s enjoyment of rent or surplus from harvested produce: both depend on (and, as in the case of the colonial monocrop plantation, often literally lead to) a moment of unsettlement, which also makes landscape—in Jean-Luc Nancy’s expression—“the space of strangeness, of estrangement . . . the opening of the space in which this absenting takes place.”[14]

Landscape, in short, represents a key ideological apparatus of capitalism and colonialism that naturalizes what are in fact violent and uneven social and political (as well as, we should add, ecological) relations, and it does so through what art theorist Alain Roger calls the “double artialization” of land—the “mobile” and the “adherent” mode of aestheticizing the earth, either rendering land as a visual prospect that can be transported from rural margin to urban site of exhibition or “relandscaping” a parcel of ground in the image of orderly nature devised by the gardener or the landscape architect: “The land, in some sense, is the point zero of landscape, it is what comes before artialization, be it directly (in situ) or indirectly (in visu).”[15] But this interplay between landscapes in visu and in situ, between journeying painters and sedentary gardeners, also corresponds to a modern-colonial dialectic of “grafting and drafting,” in art theorist Jill Casid’s expression, in which “the material practices of transplantation and grafting were part of the ordering and articulation of the Plantation as discourse,” at the same time as “the colonial landscape was planted and replanted not only through successive eras of colonial plantation but through forms of reproductive print, visual and textual, that were to serve as prototypical models of colonial relandscaping.”[16] By making its own projective (that is, presentational rather than representational) dimension appear as already found in, and emanating from, vegetable-material objects and ensembles deemed natural and orderly, landscape did its ideological work of making us enjoy the space of our own alienation. Yet this very disavowal of the unsettlement that is fundamental to the landscape form also opened up lines of flight, as in Raymond Williams’s working-class “counter-pastoral” forms of reclaiming, in a vein of utopian, future-oriented nostalgia, the working earth from which we have been displaced,[17] or in the “countercolonial landscapes” of slave orchards and queer gardenings “contesting the terrain of imperial landscaping” that Casid has analyzed.[18] By taking landscape at its word where it denies the expropriating violence that is at the very origin of the form, these subversive, oppositional deployments of the landscape in situ and in visu insist on the possibility of returning to a reciprocal mode of relating to the land, based on use rather than exchange.

Inhotim, to return to our place of departure, calls on the landscape in situ and in visu in an openly self-reflexive, critical fashion—first and foremost by bringing the beautified, gardenesque “nature” of the park back from the urban space of accumulation to the rural one of extraction that the latter both invokes and disavows. By choosing a high-modernist garden aesthetic, moreover, which finds “natural expression” in the elementary geometries of cells and organisms rather than in the image of a lost Eden preexisting the onset of the mining economy in the region, Inhotim complicates the mimetic illusion of the Western landscape tradition, instead drawing our attention to the complex affiliations and rifts between abstraction and extraction, modernism and modernity. This exercise of self-reflexivity, moreover, also continues to interpellate as we move from the gardens into the artists’ pavilions laid out along our path, perhaps most forcefully in the one dedicated to the work of Brazilian painter-sculptor Adriana Varejão (married to Inhotim’s owner Mello Paz at the time of the park’s creation), which references the region’s colonial-baroque tradition as well as the latter’s bloody foundations through the use of Portuguese azulejos (painted tiles) as its main material, the interstices of which appear to reveal not drywall, brick, and mortar but the crushed, compact mass of guts and flesh that literally supports cultural expression in the extractive zone.

In Varejão’s painting Paisagens (Landscapes, 1995) a similar simultaneous engagement with the modernist critique of representation and the baroque tradition (the greatest manifestations of which, in Brazil, are found in the eighteenth-century mining towns of Minas Gerais), explicitly singles out the landscape form as a colonial apparatus of extraction (fig. 3). Here, inside an oval (painterly rather than real) wooden frame, a tropical forest landscape is suddenly interrupted by a second, irregular frame of clotted blood surrounding a scar that is visible where the canvas appears to have been ripped open, allowing us a glimpse into the viscous entrails beneath. In the center, a second landscape, different from that of the outer ring, features a coastal scene reminiscent of nineteenth-century watercolors by traveling artists such as Jean-Baptiste Debret or Johann Moritz Rugendas. Again, the illusion of natural beauty available to the viewer is brutally sliced open by a vertical cut running across the center of the image, turning the wounded skins of canvas and landscape into a vaginal opening into the depths of a feminized earth body. This association, implied here as well as in the sequel painting, Mapa de Lopo Homem (1992)—a ripped-open sixteenth-century Portuguese world map—is instead made brutally explicit in two of the most haunting images of the same series, Filho bastardo (Bastard Child, 1992) and Filho bastardo II: Cena de interior (Bastard Child II: Indoor Scene, 1995), likewise featuring a bloody, vertical cut at the center, and depicting, in the style of eighteenth-century picturesque travelogues, the torture and rape of Indigenous and Afro-descendent women at the hands of white landowners, military officers, and priests. Paisagens, in a canny, erudite game of visual quotations, reveals rape to be the inner truth and foundational moment of beholding earth as image.

Adriana Varejão, Paisagens (Landscapes), 1993. Oil on wood. Collection of R. and A. Setúbal. Courtesy of the artist.

Varejão’s painting constantly forces our gaze to reverse course as the visual immersion-penetration, fostered by the landscape’s own rhetoric of foreground and horizon, is being counteracted by the bursting forth of bodily matter. It is the beach, in fact, the site of colonialism’s “first encounter,” that is crossed out by the vaginal scar puncturing the image’s visible skin and exposing the gutted bodyscape underneath, as if transforming the sonic pit in Doug Aitken’s nearby pavilion into a gory, and phallic, intrusion. But can art still get away with gestures like these that subtly point us—as does, indeed, the Inhotim Institute as a whole—to the artworks’ own conditions of enunciation? How, I wonder, can we even begin to reflect on the irruption of an irate, destructive Gaia at a place such as Brumadinho, which calls on nature in the name of art while also continuing to be sustained by a centuries-long cycle of destruction and ruination, by the unsavory convergence, as Moore puts it, “of nature-as-tap and nature-as-sink”?[19] Would visitors of Aitken’s pavilion unwittingly have listened to earthly forebodings of the geological movements and chemical reactions in the subsoil long before these led to the collapse of Dam 1? But how do we deal, then, with the way these subterranean rumors could only be heard—or rather, missed—in the mode of indeterminacy associated with the artwork? And, last not least, what to make of the sudden appearance of a bold new landscape architect on, or rather, underneath Inhotim’s curated grounds, one that is made of the very assemblages of mudslides and of toxic seepage into soil and ground water that will no doubt permanently alter the park’s artified landscape? Is Gaia, in fact, Inhotim’s ultimate star artist, the one who at last reveals to us the true face of the collection and botanic garden: material embodiments of the surplus capital generated from the iron ore that these same deadly chemicals had previously separated from its earthly overburden?

Perhaps the critique of landscape is now no longer in art’s hands alone. Just compare Varejão’s scarred and bruised bodyscape in Paisagens with Vinícius Mendonça’s press photograph of the Brumadinho disaster site a month after the collapse of Dam 1, featured at the beginning of this introduction. The echo of Varejão’s scar cutting through the land body of the painting, in the reddish-brown tracks of mud cutting through the lush green of the forest, is hard to miss. It is almost as if, in retrospect, Gaia had forced on us a different reading of the image, not so much as a critique of the landscape tradition of past centuries but rather as a foreboding of what is yet to come. The end of landscape, it seems, is also a moment of “return of the repressed”: of overspill onto the visible scene of what landscape had banished to the other side of the horizon. What had always been lurking at the “ground of the image,” in Jean-Luc Nancy’s expression, was an excess of presence of the more than human (that is, of the gathering of divergent lifeways and forces) that the landscape form had only been able to contain by making this ground the founding limit of its time and space of representation—in much the same way as the “extractive eye” of transnational mining companies such as Vale S. A. peers through the layers of overburden (the sand, rock, water, and clay separating the surface from the mineral veins) to get to the commodity underneath. Overburden—what is between the extractive eye and what it sees as value in and of the land—energy humanities scholar Jennifer Wenzel has argued, also offers a way of

understanding the cost of a resource logic taken to its furthest conclusion . . . If neoliberalism is understood as having largely dispensed with the promise of social good . . . then we might say that the very things that the logic of improvement and enclosure once promised as ends—civilization, civil society, the state, the commonwealth as a social compact to protect citizens and their property—now appear as intolerable commons, as unproductive waste . . . in need of privatization, resource capture, and profit-stripping. It’s all overburden.[20]

Late capitalism’s throwing overboard of the modern welfare state’s arrangements of social reproduction as themselves mere overburden might also be telling an alternative, parallel story of the development from figurative landscape to “abstraction” that differs from the one we are being told by canonical art history or even the one I have been following here through the works of Pontés, Aitken, and Varejão and through the land-scaping action of toxic mud in the vicinity of the Inhotim Art Institute. Indeed, what increasingly overburdens landscape’s capacity to capture and offer up the earth object, putting it at the disposal of the beholder, is the incremental, physical and undeniable, presence of what representation needs to cast “beyond the horizon.” The proliferation of biochemical and nuclear accidents under “disaster capitalism”[21] is only the flipside of what our imagination of world as landscape can no longer hold together in the face of an encroaching “unclean non-world (l’immonde)”—the term Jean-François Lyotard coined to name the earthly matter that landscape must keep in suspension, which it must ab-ject, to render world as object, as picture.[22] But thus, this nonworld—l’immonde, inmundo, imundo, which, in Spanish and Portuguese as well as in French, also means the filthy, obscene, reckless—is also what comes at the end of landscape. It is what landscape is itself a threshold toward, what it will usher in once everything has become overburden.

Yet this overburdening of landscape’s capacity, as a colonial-extractive apparatus, to produce subjects and objects for capitalist surplus generation, might also offer a moment of possibility, of breaking through the cocoon of landscape and of the world it has built on the back of an incremental inmundo. In thrusting human and nonhuman bodies, and even nonliving forms of matter such as rock formations and aquifers, into a shared state of precarity, uprootedness, and enmeshment, the end of landscape also puts us face-to-face with matterings that (as the giant mud wave at Brumadinho) can no longer be witnessed and inhabited as “world.” Inmundo is my term for calling out the end of the world, the “process of becoming extinction,” according to Justin McBrien, already under way with the disappearance of planetary biodiversity and of human linguistic, cultural, and spiritual patrimonies alike.[23] But it is also a way of calling for an art of survival, in which, according to Tsing, “staying alive—for every species—requires liveable collaborations.”[24] Earthwide precarity, as Tsing argues, also urges us to embrace contamination, intermingling, assemblage, as the very conditions of our survival: “The problem of precarious survival helps us see what is wrong. Precarity is a state of acknowledgement of our vulnerability to others. In order to survive, we need help, and help is always the service of another . . . If survival always involves others, it is also necessarily subject to indeterminacy of self-and-other transformations . . . Contamination makes diversity.”[25] In this book I will explore through the concept of “trance” some of these self-and-other transformations into which humans and nonhumans enter at the end of landscape, at a moment when they (or “we”) have similarly become subject to precariousness and indeterminacy. Entranced Earth, the title of the book, also names the framework I propose for reflecting on the “intrusion of Gaia” in her enigmatic and unpredictable responses “to the brutality of what has provoked her.”[26] Yet it will also provide us with a conceptual toolkit for understanding some of the emergent forms in which the arts, at the end of landscape, have responded to and embraced the challenge of recasting nonhuman lives and earthly matter as coagents rather than merely as objects or as source material of aesthetic experience.

The end of landscape, I contend, is a radically contemporary moment of the arts responding to the all but undeniable “postnatural condition” of our time,[27] and it has been a hallmark of aesthetic modernity in Latin America for at least a century. As one of the earliest extractive frontiers of the colonial-capitalist world system, the region also produced, in Déborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s expression, a host of “veritable end-of-the-world experts,” faced time and again with “a world invaded, wrecked, and razed by barbarian foreigners”[28]—a world plunged into unworld, into inmundo. Similar to the ways in which, over centuries, trance had provided an alternative space and time of gathering for the communities suffering the unworlding violence of extractivism, for some of Latin America’s most daring writers, architects, visual artists, and filmmakers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries I argue, the dimension of trance became a condition for reimagining earth as dwelling, as the journeying poets and artists of Amereida (a radical aesthetic event we will study in chapter 2) put it. Only by embracing the abysmal dimension of a continent ravaged by five hundred years of colonialism, they claimed, could the poetic event once more carve out a gathering ground on which to forge community.

Trance, as Roger Bastide suggests in his classic ethnography of the Afro-Brazilian spirit religion of Candomblé, is the ecstatic state of divine possession in which the community’s founding myths are relived, reincarnated, in the bodies of the novices undergoing initiation. The moment of ecstasy—of trance—is the one that separates and connects the first part of the ceremony, in which the heroes and events from the time of foundation are recalled by means of invocatory chanting and drumming, from the second one in which, if the session has been successful, these have yet again turned into companions and contemporaries who accompany and share the daily lives of the faithful. “What we understand as a phenomenon of possession—Bastide concludes—should therefore rather be defined as a phenomenon of transformation.”[29] The trance of Candomblé is, for Bastide, a worldmaking practice in the inmundo that unfolds in the aftermath of the world-destroying, genocidal violence of the Middle Passage and the Plantation. It turns the survivors’ bodies into bodies of resonance that bring back to life what colonialism’s necropolitical machine had sought to erase: in the time of trance, the ghosts of history become flesh once again, and this embodiment opens up a threshold of transformation, of reworlding in the inmundo.

Gilles Deleuze, in his reflections on postcolonial cinema, returns to this notion of trance to describe how the films of Glauber Rocha—the guiding spirit of Brazil’s Cinema Novo movement and director of Terra em Transe (Entranced Earth, 1968)—trigger the emergence of collective speech acts not by having recourse to myth but, says Deleuze, to “a living present beneath the myth.”[30] Similar to, yet also different from, the Candomblé priest in the terreiro (whose incantatory song and dance Rocha made the centerpiece of his filmic debut Barravento [The turning wind, 1962]), the filmmaker seizes “from the unliving a speech-act which could not be silenced, an act of storytelling which could not be a return to myth but a production of collective utterances capable of raising misery to a strange positivity: the invention of a people.” “Third-world cinema,” for Deleuze, does not represent the history of the colonized but, rather, actively contributes to their transformation into a people—into a historical agent endowed with speech—by way of entrancement (that is, by mobilizing the living present inside, or beneath, myth): “The trance, the putting into trances, are a transition, a passage, or a becoming . . . which brings real parties together, in order to make them produce collective utterances as the prefiguration of the people who are missing.[31] Trance is the assemblage, in the in-between time of ecstasy, of a future language forged from the shards and fragments of what colonial violence has suppressed and erased; a language in which new worldings can be imagined even from the depths of inmundo.

Today, at the height of what has been called a moment of neoextractivism in Latin America—one that is characterized, according to Maristella Svampa, by “the over-exploitation of natural goods, largely unrenewable . . . as well as the vertiginous expansion of the borders of exploitation to new territories, which were previously considered unproductive or not valued by capital”[32]—I contend that trance can no longer be considered, as it could for Deleuze at the height of national liberation struggles after World War II, exclusively as the realm of a becoming people. Rather, as the Argentine poet Juan L. Ortiz claims, “the people is nature,” or rather, “not nature but natural things.”[33] Poetic labor, for Ortiz (whose work we will return to at the end of this book), is “to make man participate in natural things”—that is, to force language itself to reveal how much we are always spoken by the nonhuman: “Any plant whatsoever suggests to me the relations it maintains around it . . . We think that rhythm and voice are totally ours when, in fact, they are also outside ourselves. And our very safety depends on this rhythm.”[34]

At heart, then, the question this book pursues is about the work of the aesthetic in keeping us safe—that is, about the ways in which the imagination partakes in “reknitting . . . multispecies stories and practices of becoming-with.”[35] In the face of planetary necrosis that extractive capitalism leaves in its wake, including “the disappearance of species, languages, cultures and peoples,”[36] the dimension of pleasurable but also overwhelming and painful opening to the world and the otherworldly we call art (and which, in nonwestern Indigenous cultures, is delegated in different fashion to multiple forms of play, festivity, and healing) acquires a new urgency. Capitalism is anesthetic, and it actively induces the proliferation of “unimagined communities” of human and nonhuman lives “viewed as irrational impediments to ‘progress’ [that] have been statistically—and sometimes fatally—disappeared,” as Rob Nixon has forcefully argued.[37] Extractive capitalism relies on unimagination, on “the invention of emptiness—emptiness being the wrong kind of presence,” by means of which “‘underdeveloped’ people on ‘underdeveloped’ land can be rendered spectral uninhabitants whose territory may be cleared to stage the national theatrics of megadams and nuclear explosions . . . Emptiness is an industry that needs constant replenishment.”[38]

But is it enough, then, to think of the aesthetic merely in instrumental terms, as a way of “bring[ing] emotionally to life” the long-term environmental and socioeconomic destruction wrought on the extractive zones of the planet, which the short-termism of the media cycle is both unable and unwilling to convey?[39] I do not dispute, of course, that literature, film, and visual arts can and must offer counterrepresentations to the ones advanced by extractivism’s “liberal fortune-telling,”[40] its incessant presaging of future bounty thanks to present destruction of lifeworlds. Yet I wonder if, by making the affective powers of the aesthetic or its unique capacity for self-reflexivity subservient to a political action, the purpose and content of which is already known beforehand, ecocritical approaches don’t risk relapsing into worn-out notions of art as a moral instance or as elevating the audience’s critical consciousness? Put differently, by thinking about environmental damage—or, in a deconstructive twist, by assessing its discursive figurations—as the “subject” of art, are we not still caught in an idea of “external nature” as experienced by a human subject—that is, in what Philippe Descola has referred to as the “great partition” in Western thought, which posited “nature as an ontologically autonomous domain, as a field of inquiry and scientific experimentation” and, we might add, as a source of aesthetic pleasure?[41] At the end of landscape, I contend, might we not need to attempt a different route for thinking about extractivism and aesthetics, which the concept of trance might help us figure out? In trance, there are no longer any subjects and objects: on the contrary, trance is the time and space of the one being possessed by, and becoming coextensive with, the other. Rather than on representation (and thus, on a relationship between “matter” and “form” that is itself predicated on extraction), trance draws on invocation and incarnation, that is, on “a yielding relation to the world, a mastery of non-mastery,” as Michael Taussig has so aptly put it.[42] How, I ask, can we join, as readers and viewers of texts, films, sculptures, gardens, and performances, in such yieldings, and how can these help us reengage with, according to Tsing, the “many world-making projects, human and not human” in which we find ourselves enmeshed even—or especially—at a time of encroachment of inmundo, of unworlding?[43]

To yield to the world, I shall argue, also means to let go of the distance landscape had opened between the multiplicity of living and material things and the subject. It means assuming the risk of immersion in the multiple entanglements—the “throwntogetherness” of the “event of place [as] a constellation of processes rather than a thing,” in Doreen Massey’s powerful expression[44]—to the point of shedding the autonomy and finitude that had been associated with the Western idea of art. In responding to the entranced earth, I claim, art itself becomes increasingly unspecific; it seeps out beyond the institutional circuits of galleries, publishers, and screening venues and instead begins to make common cause with community activisms, lab research, gardening, and therapy. Thus, the process of art’s becoming unspecific, which I will be sketching out in this book, also goes beyond the combination of narrative, audiovisual, and performative elements and even beyond “a strategic relationship to political collectives currently in formation,”[45] radicalizing Florencia Garramuño’s call for an “ignorant art” that deliberately renounces the knowledge associated with medium-specific styles, genres, and techniques.[46] Unspecificity, as I deploy it here, represents both a critical break with the colonial legacies of specific languages and genres and an opening toward the damaged materialities of world as remainder, in search of novel forms of community beyond the human.

In truth, then, the following chapters are but a diary or transcript of the exercises of yielding to the world in which the works and events I analyze have allowed me to participate: an exercise, as we shall see, at once of despaisamiento—of “unlandscaping,” of exhaustion of the landscape form—and of transformative crisis, of trance, in listening to the yieldings to the world ushered in by this very exhaustion. Entranced Earth is divided into four chapters covering a century of aesthetic production in Latin America in roughly chronological order. Chapter 1 establishes the extractive frontier as a focal point of Latin American cultural production in the twentieth century, focusing on a body of literary narratives classified in textbooks as “regionalismo.” In these stories and reflections, I trace the trope of an “insurgent nature” on the extractive frontier—assemblages of organic and inorganic matter, and of human and nonhuman lives, thrown into turmoil. In the work of writers such as Horacio Quiroga and Graciliano Ramos, this insurgent assemblage speaks back in strange tongues, ushering in a novel kind of interspecies free indirect speech that gives voice to a (bio)politics of communitas resisting the immunitary projects of the human colonizers. Here, I compare this “politics of nature” to the one manifesting itself in the narratives of armed struggle produced in the aftermath of the Cuban Revolution. In their different modulations of the spatial scripts of guerrilla warfare in Cuba, Guatemala, and Nicaragua, I argue, these revolutionary testimonios also recombine elements from an earlier mode of literary rainforest writing. Subsequently, I trace regionalism’s early critique of extractive modernization through a little-studied body of work: the reflections of provincial historians, scientists, and medical scholars on the impact of deforestation, soil erosion, and climate change on musical, linguistic, and material culture in the Argentine Northwest. Produced during a devastating drought, the works of these “minor intellectuals” were mourning a local milieu, the destruction of which they were witnessing firsthand, at the same time as they tried to sketch out the uncertain horizons of life after abandonment.

Chapter 2 turns from the extractive frontiers of rainforest and rural interior to the metropolitan centers of cultural production and to the manifestations of modernist aesthetics in literature, architecture, and gardening. I begin by discussing the ways in which new technologies of locomotion, especially automobility, reconfigured spatial relations and their perception as landscape in the early decades of the twentieth century. Yet, contrary to European futurism’s ecstasy of speed, the partial and uneven introduction of transport and communications technology into Latin America was reflected in narrative and poetic accounts of “accidented” movement, where acceleration was always prone to relapse into stillness. This syncopated space-time experience provoked clashes and juxtapositions reflecting the violence of the region’s entry into global economic circuits by way of resource extraction. Having analyzed the journey form and its transformations, the chapter moves to the key manifestation of the landscape in situ, the garden. Latin American architecture, I argue, reimagined the garden as a contact zone between the postcolonial city and its ecological milieu, which urbanists no longer aimed to contain or banish from the built environment but rather to reclaim as a ground for conviviality. Starting with Le Corbusier’s influential South American journey in 1929, I zoom in, first, on the latter’s impact on Argentina’s cosmopolitan avant-garde, in particular the work of Victoria Ocampo, where I trace a novel idea of the garden as an interface between self and world, first, in the correspondences between the gardens of her residences at Buenos Aires and on the Atlantic coast, and then in her writings that oscillate between autobiography and translation. Next, I compare Ocampo’s gardening aesthetics to the work of Roberto Burle Marx, Latin America’s premier landscape architect whose designs are characterized, I argue, by a problematic yet also productive contradiction between his interest in the geobotanical assemblages of a given habitat and the way organic, living forms could enter into dialogue with modern architecture’s International Style. The chapter closes with an analysis of the Open City of Amereida, a little-known Chilean architectural and poetic collective that, since the mid-twentieth century, has experimented with an idiosyncratic combination of landscape’s founding tension between place and movement. In particular, I analyze the ephemeral site interventions and poetic writings created during and after the 1965 “Travesía de Amereida,” the Amereida crossing, a transcontinental road trip that aimed to unveil the “enigma of America” through collective navigation of the “Sea Within”: a performative inversion, I argue, of the colonial trope of discovery that sought to reassert the radical indeterminacy of continental time and space.

Chapter 3 discusses what, taking a cue from Brazilian art critic Mário Pedrosa, I call “the environmental turn” in late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century Latin American art. In the first section, I analyze a series of individual and collective interventions that share an active interest in the materialities and durations of social and ecological milieus, turning these from objects of representation into material supports that determine the aesthetic event’s formal script. At the same time, the works and happenings studied here also share an unspecification of expressive forms, freely mixing elements from the visual arts and film with those of architecture, music, and poetry, often aligned with constellations of political struggle and resistance. These include the interventions of the Argentine Tucumán Arde, the Chilean CADA, and the Peruvian E. P. S. Huayco collectives between the late 1960s and early 1980s, as well as site-specific works by Artur Barrio in Brazil. Whereas the former turn the material chronotope of the city and the virtual one of mass-media networks into performative conducts, thereby blurring distinctions between the self-reflexivity of art and the transformative action of political struggle, Barrio’s distribution of abject materialities (excrement, blood, waste) in the public arena resorts to “guerrilla” strategies of clandestinity and shock as a way of forcing out the obscene that is latent in social life under dictatorship. In the following section, I analyze some of Hélio Oiticica’s work during the decade he spent in exile in London and New York City, as well as performances realized after his return to Brazil just before his untimely death. I compare these with the work of Cuban-American artist Ana Mendieta, in particular her Silueta Series of earth-body works. Despite their differences, I argue, in both artists the personal experience of displacement is channeled into an exilic, migrant ethos of reembodiment that invites the more than human into its queer and precarious placemaking assemblages. The final section of the chapter focuses on the shift in current bioart and ecoart from landscape toward the living organism and toward the habitat-building assemblages into which it enters, as constitutive of aesthetic experience. Having traced the beginnings of this shift to Luis Fernando Benedit’s ecological sculptures of the 1960s and 1970s, I fast-forward to recent work by Maria Thereza Alves, Eduardo Kac, Iván Henriques, and Gerardo Esparza where the idea of life and death as the source of form, which Benedit had been among the first to advance, is reevaluated under conditions of genetic engineering and anthropogenic climate change.

The fourth and final chapter explores “new regionalisms” in the aftermath of destruction, that is, in the inmundo unleashed on vast areas of Latin America by extractivism and neoextractivism. I begin with a reflection on soundscape as an alternative sensory response to the nonhuman environment, contrasting with landscape’s visual capture of the land object. Taking my cues from Alexander von Humboldt’s short essay “The Nocturnal Life of Animals in the Jungle,” I discuss contemporary bioacoustic production, in particular Spanish sound artist Francisco López’s piece La selva (The Jungle, 2015), whose proposition of a nonreferential, “blind listening” I contrast with the acousmatic presence of more-than-human sounds in Tatiana Huezo’s documentary film on the aftermath of civil war in El Salvador, El lugar más pequeño (The tiniest place, 2011). Here, as well as in films by Brazilians Andrea Tonacci and Gabriel Mascaro, Chileans Bettina Perut and Iván Osnovicoff, and Argentinians Verónica Llinás and Laura Citarella, which I study in the following section, “new regionalism” comes about as the stringing together of place after catastrophe, via a multisensory assemblage of human and nonhuman agents that the filmic sound image can gather thanks to its already sympoietic nature. In the final section, I bring Yanomami shaman-activist Davi Kopenawa’s testimonial account The Falling Sky—coproduced with French anthropologist Bruce Albert and first published in French in 2010—into dialogue with the political memories of disappearance in the aftermath of military dictatorship and civil war in the Southern Cone and Central America. How, I ask, can Kopenawa’s “memories of extractivism”—of mining, viral and bacteriological ethnocide, and agro-industrial land grab but, also, of the turmoil unleashed on the forest’s fragile equilibrium of bodily and spiritual lives—be heard in a political field constellated around the idea of human rights? Kopenawa’s shamanic forest memory, I suggest, might offer us a way forward toward articulating new forms of kinship between the biopolitical struggles of the postdictatorship and the challenge of “geontology” (Elizabeth Povinelli’s expression), which the present cycle of neoextractivism dares us to face up to.

Entranced Earth is a distant cousin of the homonymous book I published in Spanish some years ago, with which it still shares several subchapters and objects of inquiry. Others have disappeared or have made way for new ones, as have several of the key questions guiding my inquiry. This has come as somewhat of a surprise to me, as I had originally envisaged this book to be an only slightly reworked version of my earlier study, Tierras en trance, for an English-speaking audience. Yet in the interim between one book and the next, several things happened that forced me to consider a more comprehensive rewriting. One of these is the publication, in recent years, of several major, book-length studies on the interplay between aesthetics and catastrophic advances of anthropogenic climate change and environmental devastation—including, in the field of Latin American studies, a number of ambitious attempts to extend political critiques of extractivism and the ethics of buen vivir (or “the good life”) toward the field of cultural production and to bring these into dialogue with an emergent constellation of “environmental humanities” in the English-speaking world. To address, and to make explicit, my own position vis-à-vis this quickly expanding corpus, I have also had to reconsider and update both my primary objects of analysis and the corresponding field of critical references. But at the same time, and perhaps more importantly, the years since I completed an earlier iteration of this work also saw the emergence of climate-change denialism as a founding pillar, along with racism, religious fundamentalism, misogyny, and homophobia, of a new globalized fascism that has started to dispute the hegemony of neoliberalism, with the rise of Donald Trump and Jair Bolsonaro in the US and Brazil, respectively, and the proliferation of military-parliamentary coups throughout Latin America as the opening shots of a new round of accumulation, the violence of which will no doubt dwarf even the one unleashed by neoextractivism since the millennium. In response, this is also a more openly political book than its prequel, or at least one in which the question of politics never looms far from the surface, even as I have attempted to honor my commitment to the aesthetic as a harbinger of alternative modes of becoming with. But perhaps this distinction between aesthetics and politics is no longer sustainable in the first place and we have, yet again, reached a point where fascism’s “self-alienation has reached such a degree that it can experience its own destruction as an aesthetic pleasure of the first order,” as Walter Benjamin presciently put it in the postscript to his 1935 essay “The Artwork in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.”[47] If that is indeed the case, as Benjamin already knew only too well, then only the politicizing of art can save us.

[1] G1 Minas Gerais, “Brumadinho: Sobe para 242 o número de mortos identificados em rompimento de barragem da Vale,” G1 Minas Gerais, May 25, 2019, https://g1.globo.com/mg/minas-gerais/noticia/2019/05/25/brumadinho-sobe-para-242-o-numero-de-mortos-identificados-no-rompimento-de-barragem-da-vale.ghtml.

[2] Leonardo Fernandes, Lu Sodré, and Rute Pina, “Beyond Mariana and Brumadinho: Vale’s Long History of Violations,” Brasil de Fato, February 1, 2019, https://www.brasildefato.com.br/2019/02/01/beyond-mariana-and-brumadinho-vales-long-history-of-violations.

[3] Shasta Darlington and Manuela Andreoni, “A Tidal Wave,” New York Times, February 9, 2019, of Mud,” New York Times, February 9, 2019, https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/02/09/world/americas/brazil-dam-collapse.html.

[4] Camila Costa, “Brumadinho: Brasil tem mais de 300 barragens de mineração que ainda não foram fiscalizadas e 200 com alto potencial de estrago,” BBC Brasil, January 31, 2019, https://www.bbc.com/portuguese/brasil-47056259.

[5] Bruno Latour, Facing Gaia: Eight Lectures on the New Climatic Regime (Medford, MA: Polity Press, 2017), 112.

[6] Steve Lerner, Sacrifice Zones: The Front Lines of Toxic Chemical Exposure in the United States (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2010).

[7] Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2015), 23.

[8] Norman Bryson, Vision and Painting: The Logic of the Gaze (Basingstoke, England: Palgrave, 1983), 96.

[9] Jason W. Moore, Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital (London: Verso, 2015), 170.

[10] Timothy Morton, Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 99.

[11] Isabelle Stengers, In Catastrophic Times: Resisting the Coming Barbarism (Ann Arbor, MI: Open Humanities Press, 2015), 53.

[12] For a short documentary video of Sonic Pavilion created by the artist, visit https://vimeo.com/152320997.

[13] Denis E. Cosgrove, Social Formation and Symbolic Landscape (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998), 15).

[14] Jean-Luc Nancy, The Ground of the Image, trans. Jeff Fort (New York: Fordham University Press, 2005), 60.

[15] Alain Roger, Court traité du paysage (Paris: Gallimard, 1997), 18.

[16] Jill H. Casid, Sowing Empire: Landscape and Colonization (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2005), 2.

[17] Raymond Williams, The Country and the City (New York: Oxford University Press, 1976), 300.

[18] Casid, Sowing Empire, 191.

[19] Moore, Capitalism, 280.

[20] Jennifer Wenzel, “Afterword: Improvement and Overburden,” Postmodern Culture 26, no. 2 (January 2016), doi:10.1353/pmc.2016.0003.

[21] Naomi Klein, The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism (New York: Picador, 2007), 355.

[22] Jean-François Lyotard, The Inhuman: Reflections on Tim, trans. Geoffrey Bennington and Rachel Bowlby (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1991), 187.

[23] Justin McBrien, “Accumulating Extinction: Planetary Catastrophism in the Necrocene,” in Anthropocene or Capitalocene? Nature, History, and the Crisis of Capitalism, ed. Jason W. Moore (Oakland, CA: PM Press, 2016), 116.

[24] Tsing, The Mushroom, 28.

[25] Tsing, The Mushroom, 29.

[26] Stengers, In Catastrophic Times, 53.

[27] T. J. Demos, Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), 101.

[28] Déborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, The Ends of the World, trans. Rodrigo Nunes (Cambridge: Polity Press, 2017), 107.

[29] Roger Bastide, Le Candomblé de Bahia: Transe et possession du rite du Candomblé (Brésil) (Paris: Plon, 2000), 220.

[30] Gilles Deleuze, Cinema 2: The Time-Image, trans. Hugh Tomlinson and Robert Galeta (London: Athlone, 1989), 222.

[31] Deleuze, Cinema 2, 22–24.

[32] Maristella Svampa, Neo-Extractivism in Latin America: Socio-Environmental Conflicts, the Territorial Turn, and New Political Narratives (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 7.

[33] Juan L. Ortiz, Una poesía del futuro: Conversaciones con Juan L. Ortiz (Buenos Aires: Mansalva, 2008).

[34] Ortiz, Una poesía del futuro, 45.

[35] Donna J. Haraway, Staying with the Trouble: Making Kin in the Chthulucene (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016), 55.

[36] McBrien, “Accumulating Extinction,” 116.

[37] Rob Nixon, Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 153.

[38] Nixon, Slow Violence, 165.

[39] Nixon, Slow Violence, 14.

[40] Ericka Beckman, Capital Fictions: The Literature of Latin America’s Export Age (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013), 16.

[41] Philippe Descola, Par-delà nature et culture (Paris: Gallimard, 2005), 107.

[42] Michael Taussig, The Corn Wolf (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 141.

[43] Tsing, The Mushroom, 21.

[44] Doreen Massey, For Space (London: Sage, 2005), 140.

[45] Grant H. Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2011), 28.

[46] Florencia Garramuño, Mundos en común: Ensayos sobre la inespecificidad en el arte (Buenos Aires: Fondo de Cultura Económica, 2015), 38.

[47] Walter Benjamin, Illuminations: Essays and Reflections (New York: Schocken Books, 1969), 20.